Sunday Pastries With the Dead 47

The est. 1668 Eastern Cemetery in Portland, ME.

I recently took myself to Maine for the very first time, and a must-visit stop was Portland’s Eastern Cemetery, which is the oldest burial ground in the city—it was established in 1668 and there are almost 7,000 people interred within. I was there in early May when the graveyard wasn’t yet open to the public for the season, but the lovely team at Spirits Alive—a volunteer-run organization dedicated to preserving the cemetery and educating visitors about its history—unlocked it for me so I had exclusive access to explore the grounds.

Special thanks to Jeff Lyons, Spirits Alive president and tour program manager, for joining me to offer countless fascinating facts about the cemetery. There’s nothing like nerding out over headstones with a fellow taphophile! I encourage you to donate to Spirits Alive or buy some of their merch (I’m now the proud owner of a death’s head logo sweatshirt!)—it’s so important to support the people who preserve these priceless places. My work would be nothing without groundkeepers, conservators, operations coordinators, and historians—many of whom rarely receive acknowledgement.

The cemetery is located in Portland’s Munjoy Hill section, elevated with some peek-a-boo views of Casco Bay. There are so many gorgeous slate headstones to peruse, it feels overwhelming at first. After about an hour of general wandering, I got my bearings and was able to double back and really focus on the standouts.

Just inside the main gate is a white shed with adorable decorative roof gable trim—its cute exterior would never tip you off regarding what’s inside: the entrance to the cemetery’s underground receiving tomb. The tomb was built around 1850 and used for 40 years, temporarily storing those who died in the winter when the ground was too frozen to dig. The arched space is 21 feet long, 11 feet wide, and 7 feet tall, with a capacity for up to 80 coffins. Now, it holds groundskeeping equipment. To my delight, the shed is known as the “Dead House.”

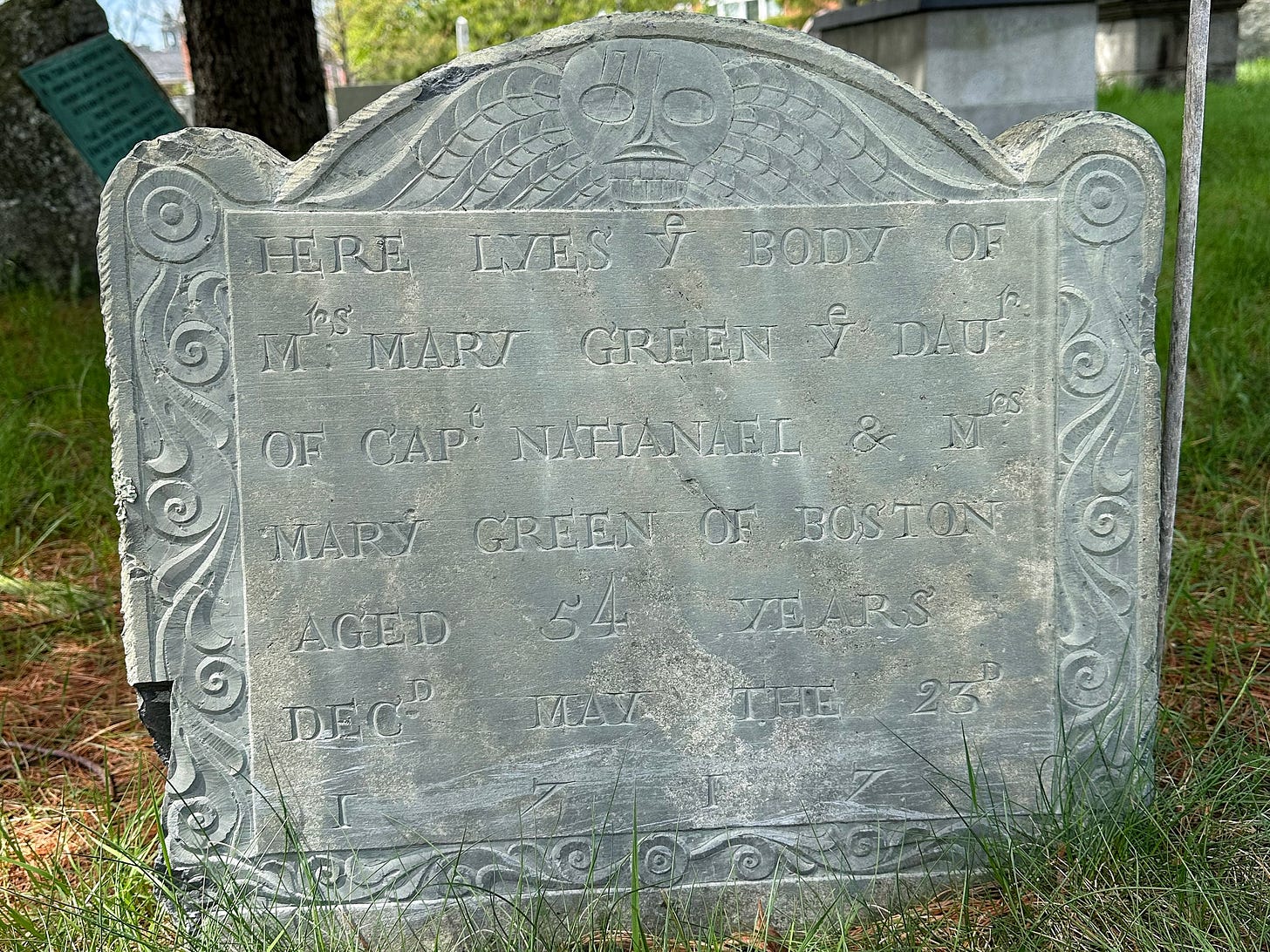

The oldest surviving stone in the cemetery is that of Mary Green, who died at age 54 in 1717. This looks a lot like a John Stevens shop stone to me (which would’ve been transported from Newport, RI by water), though I have yet to find proof.

The most prolific carver represented here (by a country mile!) is a Massachusetts-born and trained stonecutter named Bartlett Adams, whose iconography often includes urn, rosette, and sun design elements. He ran a bustling shop from 1800 to 1828 that was just a 10-minute walk from Eastern Cemetery. The location is pictured above (along with a few examples of his stones), though the original building Adams and his team worked out of was destroyed in the city’s great fire of 1866. Adams was the first stonecutter in Portland—he and his shop apprentices (eight in total over the years, including his brother and two nephews) are responsible for one third of the gravestones in the cemetery (that’s roughly 700!)

The stone Adams made for his first-born son, who died at just five months old in 1806, is his most well-known—the intricate tympanum carving reflects his take on their family crest. The stones of his son George (died 1809) and daughter Eliza (died 1812), pictured in the above left photo, are much simpler. Perhaps Adams’ workload had picked up significantly by then and he didn’t have as much time to commit to their creation, or maybe—since they both died at birth—he hadn’t grown quite as attached to them. Bartlett, who died in 1828, is also buried here with the rest of his family in an underground tomb, but it ironically has no grand marker; the original ledger stone atop it is long gone.

There are too many incredible Adams stones to include here, so consider this my attempt at compiling some of the best. I’m fascinated by both the varied stone shapes and stunning carving techniques. Aside from urns (leaving the material body), curtains (the veil between life and death), torches (life being snuffed out), willow trees (mourning), and soul effigies (the soul ascending to heaven), the top left design also pictures Hope, one of the seven virtues, signified by the anchor she’s holding and depicting the soul’s voyage elsewhere. I also had my first spotting of a symbol that looks like an umbrella (bottom right). The heart framing on the bottom left stone reminds me of the Ebenezer Price carvings in Westfield, NJ’s Presbyterian Church Burial Grounds.

There are many other stones here created by Bartlett’s employees, including several Alpheus Cary stones (top row) and others generally attributed to his shop (bottom row). Gratitude to Adams researcher Ron Romano for his detailed survey, which helped me identify all the Adams shop stones I photographed.

Jeff relayed this fun fact during our walk: Captain Joseph Greenleaf (recipient of a coveted Bartlett Adams headstone) was the very first lighthouse keeper of the nearby Portland Head Light, one of the most famous lighthouses in Maine. He was appointed in 1791 by President George Washington, and died of a stroke in 1795 while boating on the Fore River. His plot had a view of the lighthouse until recently, when housing was constructed at the edge of the cemetery.

You may recognize the last names on these gorgeous stones, both carved by German-born, Boston-based Henry Christian Geyer. They’re for Tabitha and Stephen Longfellow, the great-grandparents of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who was born in Portland.

There are some excellent examples of cenotaphs here, which are monuments to people buried or lost elsewhere. These were common at a time when infrastructure didn’t allow for easy transport of bodies, especially those who died at war or sea. The Bartlett Adams-carved stone on the left, for William Knight, explains that he died in 1806 during his passage to Portland from St. Bartholomew’s. The Adams-carved stone in the center, for Captain James Weeks, says he died in 1809 on his ship while sailing from Portland to Jamaica. The right-most stone, made in Adams’ shop (likely by Alpheus Cary) may possibly be a cenotaph, as it says Mary Stonehouse “drowned from the Portland Packet” at Richmond’s Island in 1807—it’s unclear whether or not her body was washed up and interred here. This also counts as a calamity stone, since it lists the untimely manner of death. ***Edit—care of Jeff’s comment below, and Ron’s amazing research, it is clear that Mary is buried in the cemetery—here’s a fascinating article about the shipwreck.***

Continuing the cenotaph tour, above left is the stone of Captain Joseph Weeks, who died on his passage from the West Indies in 1797, as well as his son Daniel, who was “lost on board the Brig Dash” in 1815. The right two images are a marker for Sergeant Alonzo Stinson, who was the first soldier from Portland killed in the Civil War. He died at age 19 in 1861 at the Battle of Bull Run in Virginia (his body still resides there). This is the second time I’ve seen a rucksack memorial design—the first was at Albany Rural Cemetery.

I was also delighted to find two mistake stones. Else Plummer’s, likely a spelling error, has been cleverly disguised by depressing her entire name section to make the re-carving appear as a design flourish. And Jane S. Williams’ stone includes a cutout replacing a previously incorrect middle initial.

And, because I can’t help myself, I’m closing out with a rapid-fire of some of my favorite soul effigy and death’s head carvings. There were dozens of each to choose from, so I landed on trying to cover a breadth of different carvers.

That’s all for this latest cemetery visit—thanks for joining me! If you love these posts and want to help fund my research and reporting, you can upgrade to an optional paid subscription below. Until a future Sunday, fellow taphophiles!

Thanks for visiting us, and for sharing so many of the beautiful stones found in Eastern Cemetery. For more detail on Mrs. Stonehouse, who IS buried in Eastern, and the wreck of the "Portland Packet" (actually the schooner Charles) see this paper by Spirits Alive Historian Ron Romano on our website: https://www.spiritsalive.org/special/papers/03_Wreck_Schooner_Charles.htm#eighteen

Thanks Katie! Fascinating! I love your Pastries with the Dead articles.