Sunday Pastries With the Dead 1

The 1730-era Old Bethlehem Presbyterian Churchyard in Grandin, NJ.

The first time I walked through this graveyard three years ago, I had a distinct feeling that its occupants wanted me to join them posthaste.

I was there to take a self-portrait, and I knew immediately that I wasn’t welcome. I broke out in full-body goosebumps, saw shadows lurking out of the corners of my eyes, and—while arranging to stand on the old stone wall that runs its perimeter—abandoned my plans when the image of me falling and breaking my neck flashed in my mind.

I left quickly, and considered the locale the most sinister cemetery I’d ever had the displeasure of setting foot in. I realize now that I’d waltzed in there for selfish reasons, laser-focused on getting the shot without stopping to pay my respects—and I’d upset some of the deeply traditional church elders in the process. So today, for the first official year two SPWTD post, I decided to try for a truce.

I know so much more than I did back then—through my formal study of spiritual mediumship and my 47 cemetery visits in the first year of this series, I’ve transformed my relationship with the dead. I arrived today with a healthy smattering of historical research under my belt, prepared to ingratiate myself.

As is tradition, now, I first walked the perimeter to introduce myself—explaining right away that I knew the last time I visited I was rude, and I was sorry. I nibbled my pastry as I strolled, describing its flavors and textures. The dead love being reminded of food—butter, especially, tends to be a hit with folks of all eras.

But, as I rounded a corner and took a bite, the entire center of my pastry bottomed out and fell at my feet. I sensed snickering all around me. So this would be my penance. I nodded, smiled, and pulled two pages of notes from my back pocket. I first spoke to the original pastor of the church, thanking him for fostering a tight-knit congregation that remains fiercely protective of their space. I said I’d be working my way through to say hello to everyone, but that I had a list of people I was especially interested in meeting. I then read out all the names, roll call-style. I sensed a softening.

This cemetery was established alongside a log meeting house built in 1730 (it’s long gone, but was once situated in the area pictured above left; the northeast corner of the old graveyard). The present-day iteration of the church (pictured right), built in 1870, now sits across the street. The founding Presbyterian congregation sent three members to a Sons of Liberty meeting in 1766, supported the Continental Congress in 1774, and 22 of its members fought in the Revolutionary War. They were a proud bunch, so I treated my visit with the added reverence they required, and it was a far more pleasant experience this time.

The oldest death dates I could read were these two from 1763. The right-most stopped me in my tracks—this four-hour-old little boy was clearly very loved, as evidenced by his high-quality sandstone memorial, which has miraculously stood the test of time. It also depicts an excellent example of the early Death’s Head symbol—first used to portray the decidedly grim puritan outlook that life was fleeting and death was forever, and later softened to depict human and cherub faces with wings (symbolizing the soul’s flight to heaven) as the church’s stance on death softened.

Above are six of the 22 congregation members who served in the Revolutionary War. I used old church records to source these names (I got lucky—it’s pretty rare that these types of documents remain).

Jacob Anderson, also a Revolutionary War veteran (and a Captain, at that!), built the stone wall that surrounds the graveyard in 1793. It was rebuilt in 1874 using the same stones and still stands today—a bit battered, but undaunted.

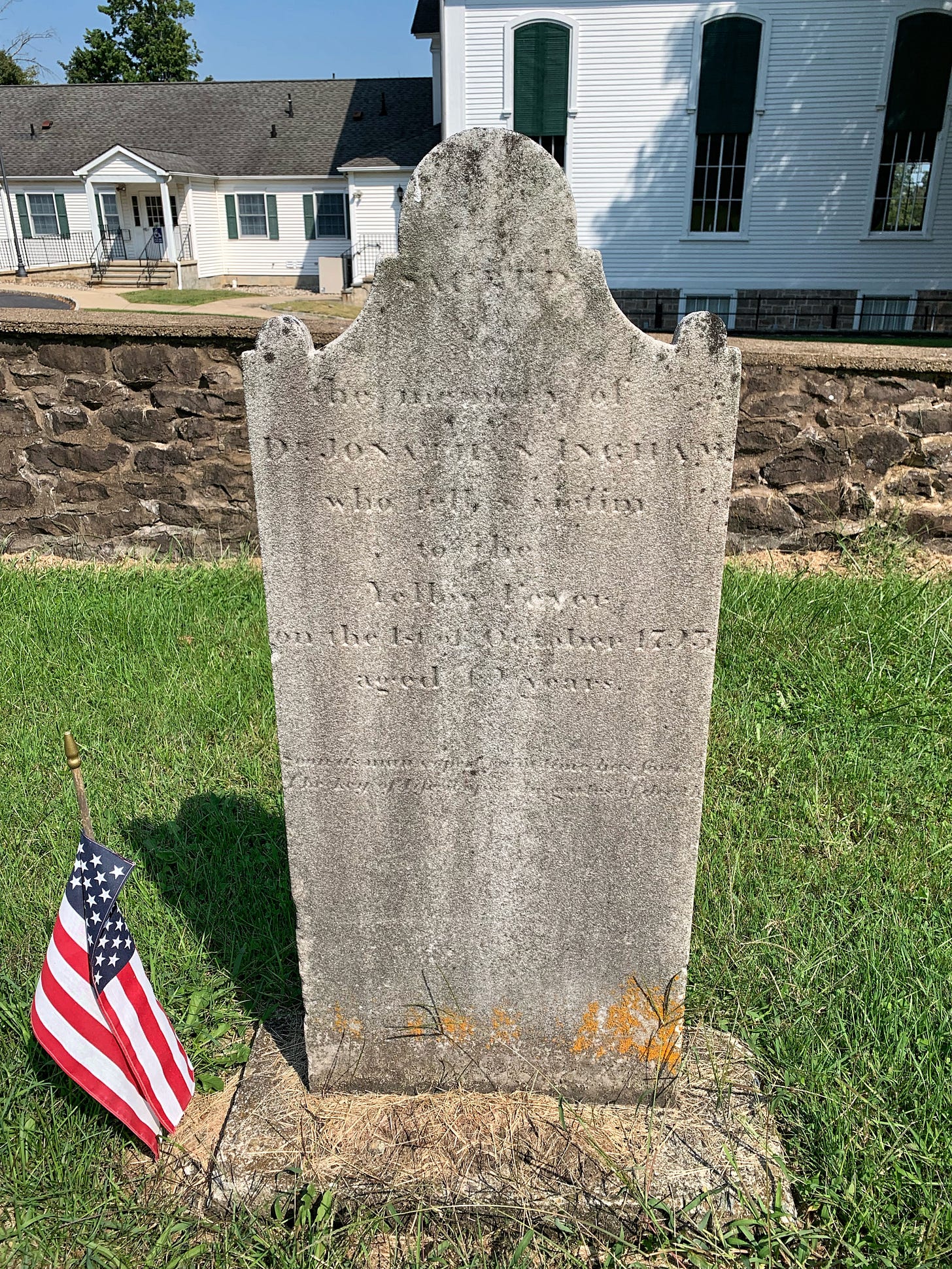

This gravestone gave me pause—it’s rare to see a cause of death listed on a marker, and yellow fever is so dramatique. Dr. Jonathan Ingham II operated a nearby farm and textile mill while also practicing medicine and teaching at Princeton University. He sheltered George Washington and his troops at his estate in 1776, where he attended to the sick and wounded. He contracted yellow fever in Philadelphia while treating patients during the widespread 1793 epidemic; he later died in his wagon attempting to reach a nearby mineral spring, which he’d hoped would cure him. Because people feared catching the plague, no one would go near his body—his wife and slave dug his grave and buried him in this very spot in his plain clothes, wrapped in his bedding in lieu of a coffin, which couldn’t be delivered in time.

One of my favorite things about old headstones is the varying vintage fonts. These are three excellent examples from today’s outing.

All in all, this was a fitting location to kick off the memorialization of a weekly tradition that once solely lived in my Instagram stories. My relationship with this place feels full circle—I know now that, unlike the symbolism on the graves, the emotions emanating from their occupants aren’t set in stone.